A highlight of this for me was the writing; Samuel Fisher can really turn in a sentence. Here’s an example from the opening: The ice that clung to Patrick’s eyelashes was flushed claret. This garishness – rimming his unseeing eyes, fixed on the ice below – made Joe think of the wooden heads that hung in the rafters of St. Mary’s: the painted faces of dead aldermen who funded the church’s restoration, now watching over their descendants. He thought of the way their rictus and rough cheeks mocked the solemnity of the place. Here and in the rest of the novel, his use of language is wonderfully precise. Reading the extract on the blurb was what made me interested in the first place, and it was worth it for that reason alone.

The book is an examination of how a community is affected by disaster. The dual perspectives work to give a broad sense of how it functions and what changes as a result of the murder. The focus is on the characters and their emotional responses to what’s happened, rather than being a whodunnit.

Fisher creates a vivid sense of place, making his fictional Wivenhoe feel lived-in and believable. This alternate world is a hair’s breadth away from our own, slowly succumbing to climate change, with a government that pays no attention. The politics of the novel are clear but unobtrusive, with Fisher allowing the story to speak for itself. As events unfold, the source of the damage done to the community is shown to be complacency, on both the political and the personal level – letting things slip by unchecked until it’s too late.

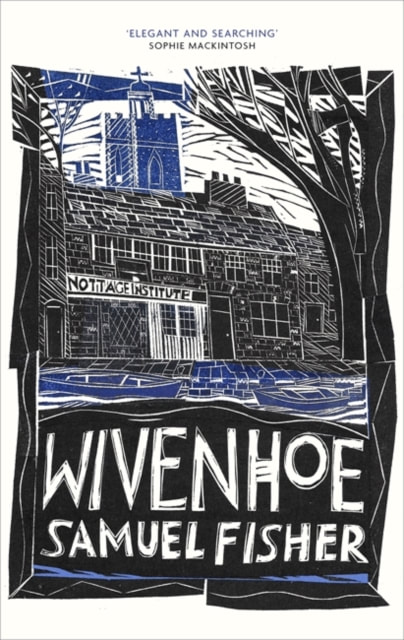

Wivenhoe is the hometown of Samuel Fisher, and it shows in the detailed way he depicts the place. This is his second book, after his debut novel The Chameleon, which came out in 2018 and was shortlisted for a number of awards. I’m keen to check it out, on the strength of Wivenhoe, and excited to see what he writes next.

Review by Charlie Alcock

RSS Feed

RSS Feed