What makes this novel excel beyond the reigns of a typical psychological thriller is in its sensitivity and its attention to detail. Vásquez silk-like writing has an immense talent for picking out historic details that other authors would have missed. The book even opens with an account of a hippopotamus that escaped from Escobar’s personal exotic zoo after the mob kingpin was killed. And Vásquez uses these overlooked details as the coat-hangers for his narrative. The result is a very impressive, tightly knitted, utterly unpredictable brand of storytelling, which manages to pull away from the big picture of Colombian violence, and bring real tangible life to those souls caught in the crossfire.

While Vásquez is clearly a very talented writer, it must be said that there are occasions where his particular virtuoso style goes a bit too far. Every so often, he lingers on unnecessarily poetic tangents and strays into musings that were better left unsaid. Mostly, these are brief throwaway phrases that can be overlooked, but the hundred-page flashback to Laverde’s youth is certainly a mismanaged offence. It’s not that this section of the book is bad, only that it is far more pedestrian and far less emotionally charged than the main plot, whose riveting momentum it stops right in its tracks.

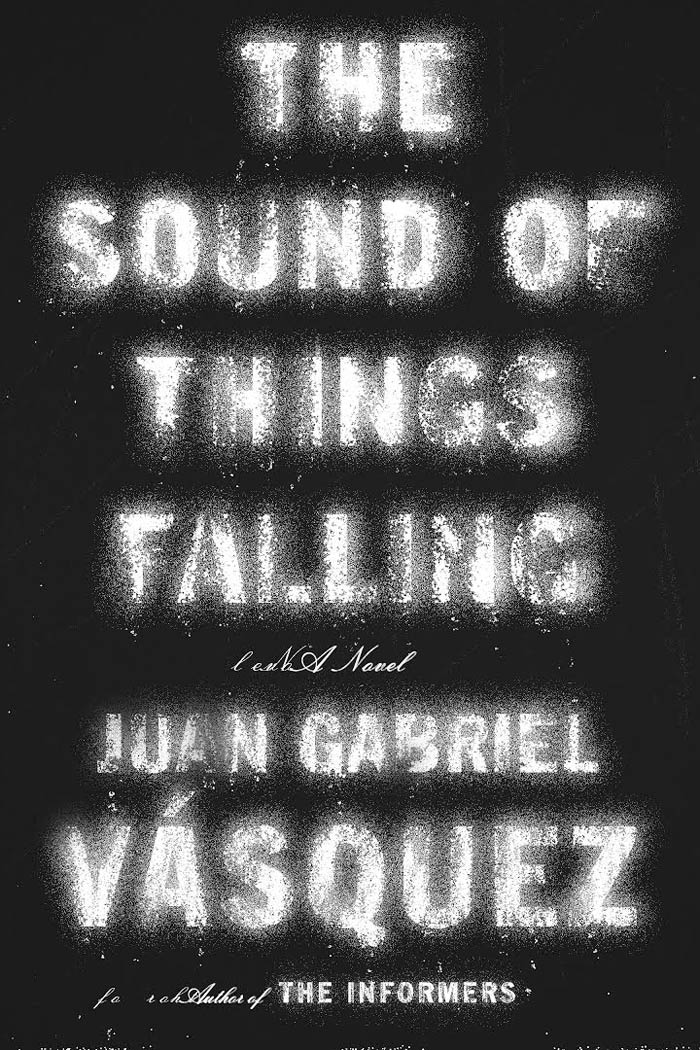

However, each act of this novel, of which there are six, bleeds with a history and a culture mostly unknown to the average European reader. And the plot and pace of the text is secondary to this. What matters more to Vásquez is that his country is bruised, but not beaten, his people hurt, but still standing. In a discourse so often hijacked by the whirlwind of Escobar’s cocaine trade, The Sounds of Things Falling gives a powerful, nurturing voice to the everyday citizens who were left to clean up his mess.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed