There are two angles from which we can view this unearthed text. Firstly, as a dystopia. What is interesting here is that the metropolis is incredibly diverse, with Budai observing that there is no suggestion as to which race or ethnicity makes up the majority of the population. And yet, despite this, the landscape still feels monotonous, and aggressively so, as Karinthy portrays Budai’s attempts at navigating the maze growing more and more hopeless with every page. The environment created is so brutal and unpleasant that the actual reading experience can feel quite exhausting at times, like the mysterious city is grinding us down as well as Budai. There are striking similarities, in this respect, to George Orwell’s classic Nineteen Eighty-Four, though Metropole is far more hostile and far less overtly politically charged. Often, it feels like the population are acting horribly for the sake of acting horribly, and it’s unclear exactly what point Karinthy is trying to make. Is this a vision into a multi-national future? Is this a satire of today’s existing megacities? Or is this a purely apolitical dive into an idea of hell? There’s room for interpretation, though the lack of concrete direction can leave the reader feeling a little lost.

But we can also view Metropole as a study of linguistics. Watching Budai attempt to decipher this bizarre language from scratch allows for some quite fascinating exploration into other European languages and how they have developed over the centuries. We get to learn factoids that most of us English folk are blind to, such as how Bulgarian verbs operate. But while Karinthy presents these asides in ways which are interesting and accessible, it is not an area of knowledge that every reader is going to find engaging.

And that feels like the crux of this novel: it’s very niche. Combining the dystopian and linguistic aspects of it, Metropole places itself in a fairly unique pigeonhole, one that I feel only a handful of people could enjoy to its fullest extent. To those of us outside the niche, this book can feel strange, stressful and not altogether that enjoyable, though I’m certain Ferenc Karinthy had no intention of it being a pleasant read.

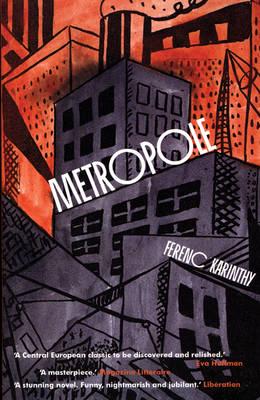

Metropole is produced by Telegram: https://saqibooks.com/imprint/telegram/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed